Mobile Health Apps Continue to Make Headlines

Recently published studies are illustrating the types of issues that mobile health application, or "app," developers will continue to face as the industry matures alongside an evolving regulatory and enforcement landscape.

Study Questions Privacy Policy of Some Mobile Health Apps

Last week, researchers at the Illinois Institute of Technology Chicago-Kent College of Law published a study about the privacy protections of mobile health apps. The study, which analyzed diabetes applications available for download from Google Play (that is, for use on mobile platforms running the Android operating systems), found that over 80% of the diabetes apps had no privacy policies. Further, over 86% of the apps without a privacy policy shared sensitive data with third parties. In addition, nearly 80% of the apps that did have a privacy policy nevertheless shared user information with third parties. Such user information, the researchers note, routinely includes sensitive health information such as insulin and blood glucose levels. The researchers point out that app developers often sell the information to data aggregation companies, who in turn sell it to credit card issuers, life insurance companies and other third parties.

Study Finds that Some Mobile Health Apps Do Not Function As Advertised

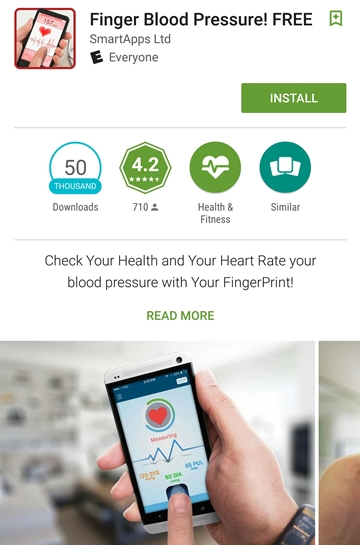

Some app developers are also facing increased scrutiny on a more fundamental issue: the functionality of their apps. Researchers at Johns Hopkins recently found that one of the most popular mobile apps used to measure blood pressure was wrong 8 out of 10 times. The app, called “Instant Blood Pressure,” is no longer available for purchase, but users who previously downloaded it are still able to use it. The app measures blood pressure by having the user place their finger over the camera while placing the phone's microphone on their chest. Other apps, including the one below, measure blood pressure through other means:

While some apps like Instant Blood Pressure contained disclaimers that the app was only meant for "Entertainment Purposes," others, including the one pictured above, contain no such disclaimer. Mobile app developers should examine their claims and disclaimers closely, as the failure to properly label and describe the functionality and limitations of an app could lead to potential enforcement measures.

Federal Efforts to Spur Adoption Uncover Limited Reach and Uncertainty Over HIPAA

The growth of mobile health apps is occurring alongside federal government initiatives to spur their adoption. Last year, the federal government announced that it would require electronic health record (EHR) systems to include an application programming interface, or API, in order to be certified under the Meaningful Use program. An API would enable other applications, like mobile medical apps, to interact with the EHR system. According to CMS, the increased use of APIs will:

Enable the development of new functionalities to build bridges across systems and provide increased data access. This will help patients have unprecedented access to their own health records, empowering individuals to make key health decisions.

Patient empowerment is, to be sure, a laudable goal. It is also undisputed that there are potential benefits to mobile health apps. It is less clear, however, how existing law regulates the health and medical app marketplace. Take for example the diabetes apps that sell user data, as identified in the study described above. The primary federal law protecting health information— the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)—applies only to health care providers, health insurers, health care clearinghouses, and the business associates of such entities. So a developer offering a diabetes app on behalf of an insurer would have to abide by HIPAA, but a developer independently offering such apps to the general public would be outside of HIPAA's reach and would not be subject to mandatory patient privacy laws at the federal level. Further complicating matters is the difficulty that the industry has encountered when trying to determine whether HIPAA applies to their particular app product. Fortunately, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recently released guidance that analyzes various scenarios involving medical apps and whether HIPAA applies.

Federal Enforcement Paradigm

The issue of non-functioning apps is largely a matter for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to oversee under their respective existing authorities. In 2013, FDA released a 44 page guidance document discussing its approach to regulating mobile medical apps as medical devices under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA). In its guidance, FDA outlined the categories of apps that it considers to be subject to regulatory oversight as a medical device. One of these categories corresponds to "mobile apps that transform the mobile platform into a regulated medical device by using attachments, display screens, or sensors or by including functionalities similar to those of currently regulated medical devices." However, FDA also made clear in its guidance that it will exercise enforcement discretion in cases where a medical app poses a low risk to the public. Jennifer Rodriguez, an agency spokesperson, recently told Wired magazine that:

The FDA is focusing on a small subset of mobile apps that are medical devices and present the greatest risk to patients if they do not work as intended. For that subset, the FDA might take action were it to determine that an app does not meet relevant regulatory requirements. But our typical approach would be to allow a firm to come into compliance voluntarily before taking enforcement action.

The fact that there are hundreds of mobile apps currently being offered on the various app stores without having gone through FDA medical device review indicates that the agency does not currently have the resources to police all market entrants, including those apps that potentially meet the criteria for being regulated as a medical device. The agency has also been criticized for offering only recommendations for implementing medical device cybersecurity controls rather than mandatory regulations for the industry to follow. This same criticism can apply to the regulation of app-based devices, which suffer from the same potential hacking and malware risks associated with more traditional (but connected) medical devices.

Developers Face Uncertain, Yet Potentially Large Liability

Even though FDA oversight and enforcement resources are presently stretched thin, developers still face potential liability for unsubstantiated, false, or misleading advertising claims under the FTC Act and, as we noted above, for the scope and content of their privacy policies and data sharing activities. For example, in 2012, Google agreed to pay $22.5 million to settle FTC allegations that that its privacy policies were misleading. In a separate case last year, Google agreed to pay $8.5 million dollars to settle a class action lawsuit accusing it of improperly selling user data. In light of the increased scrutiny of all aspects of mobile health/medical apps—whether from government agencies or consumer-protection advocates—developers of such products should conduct a thorough legal assessment before making their apps available for download.