The Beauty and the Terror of Agile Software Development

“This vendor is great, they use agile!” Clients often come to counsel with this mindset when they are buying development services, where “agile” is a label that implies a better, more streamlined approach. But while an agile approach offers a variety of benefits versus traditional, “build to spec” software development, it necessarily shifts certain contractual risks to the client, which can result in cost creep and disputes.

What Is “Agile” and Why Should Lawyers Care?

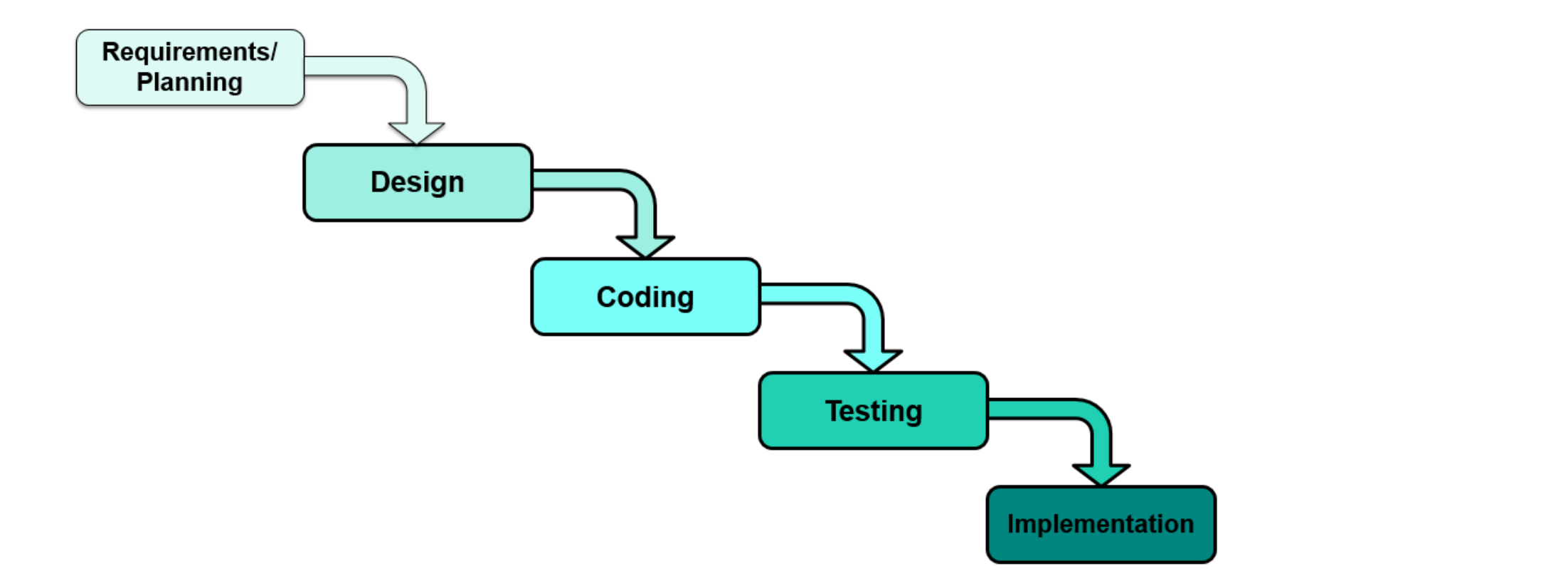

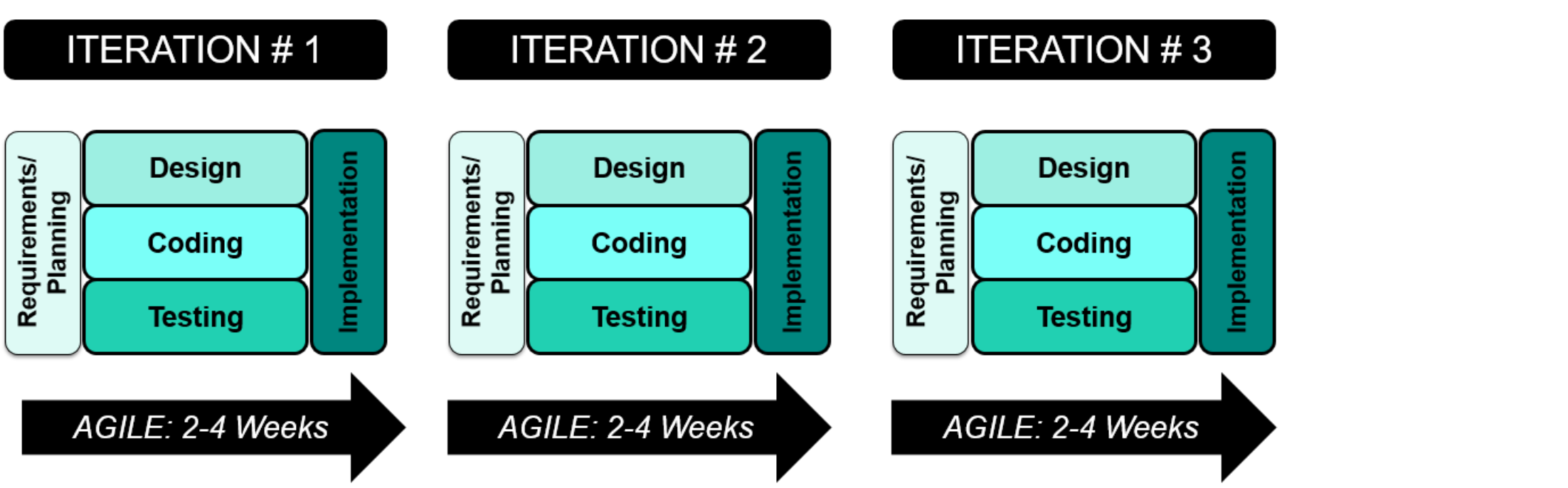

“Agile” is an umbrella term for software development frameworks that emphasize collaboration and adaptation, versus the “waterfall” or “build to spec” methodology of a traditional software development framework. Instead of moving through the various stages of development (specifications, design, coding, testing, and implementation) sequentially, development is broken out into a series of sub-projects called “iterations” or “sprints.” Each sprint lasts a short time (typically two to four weeks) and should result in a fully functional, deployable piece of the overall project. Each sprint contains the same elements as the waterfall methodology, except that the designing, coding, and testing of the sprint take place largely simultaneously. The resulting process is much more flexible than a traditional waterfall process, but relies heavily on client involvement and a well-facilitated process in order to be successful.[1]

Waterfall development:

Agile development:

Agile Contract Challenges

By its nature, an agile process is iterative and puts more responsibility on a client than a traditional approach. Here are some of the key contracting issues that will present themselves in the agile context:

Uncertainty. In agile development, final specifications are not agreed upon up-front; in some cases, the very nature of the final product itself is not specified at the outset of the project. Instead, agile development will focus on the high-level description of what the client wants the final product to accomplish, and will then establish an iterative process of development and client testing and refinement to get there. At the time of signing the contract, the client will not know (and will not be able to hold the developer to) exactly what the end result will be.

Timing & Pricing. Because the specifications are not agreed upon up front, time-to-completion and pricing can be moving targets. Clients often want certainty as to the cost and development time involved in a project, but developers do not want to commit to a fixed price or timeline when there is no final specification against which to estimate.

Rights & Obligations. The collaborative nature of the agile framework also means that the rights and obligations of the developer and client can become blurred. Because the client is heavily involved in the review, approval, and re-scoping of the agile project as it progresses, there is increased opportunity for the developer to blame the client for scope creep, changing priorities, or delays. This can limit a client’s ability to seek remedies against the developer.

Best Practices

Prepare for the commitment. By its nature, agile development involves a lot more of a client’s internal employee time than traditional software development: the client must participate in regular meetings and product testing, and is responsible for re-evaluating its own goals and needs in order to adequately direct the agile team. Ideally, the client will allocate an internal resource who has experience handling agile development matters to direct the project (usually called the “product owner”) to ensure that both client and developer resources are being deployed efficiently.

Use the right starting point. Most development contract templates or master services agreements (MSAs) are tailored towards the traditional waterfall development structure, with sequential development phases, longer times between deliverables, and project requirements that are detailed up-front with either a fixed price or a series of phased estimates. Instead, clients should use an MSA, and statements of work underneath the MSA, or SOWs, that are purpose-built to handle an agile development process. As we describe below, a purpose-built agile development contract should be more process-oriented than a traditional MSA/SOW combination, and should include definitions of nomenclature and provisions that specifically mitigate some of the risks of agile development.

Know (and define!) the nomenclature. Agile comes in many flavors and involves a lot of jargon, but it is critical to stick to the core contracting principle of defining all key terms within the four corners of the contract. Documents that come from an agile developer (particularly SOWs) may use jargon like “weekly stand-up,” “scrum master” and “backlog.” While some of these terms have widely accepted definitions, specifically defining them within your contract is critical for avoiding ambiguity and disputes.

Focus on mitigating the specific contracting challenges presented by agile development. For example:

- To mitigate the risk that the iterations do not work together or as expected, the MSA should include a warranty that each iteration will work with all other iterations, that the final product will conform to expectations set out in each SOW, and that the iterations will be designed to advance the overall project vision defined in the SOW.

- The client should be able to terminate the contract and take all work product for any or no reason at the conclusion of any iteration. Cancellation fees, if any, should be nominal because the narrow focus and short time frame of each iteration means that the development teams should be leanly staffed and easily able to transition to new projects.

- Each iteration should still be delivered to, and owned by, the client at the conclusion of each sprint, and in the event of termination, the developer should commit to spending additional time training the client in how to finish the deliverable at the developer’s then-current consulting rates.

Rigorously define your process. A good agile contract is ultimately a process-oriented document because the substance of the development is continually iterated upon and redefined. It is unwieldy to execute a new SOW with specifications for each sprint; instead, SOWs can define each high-level goal, and establish detailed processes by which development will take place. These details should include specific meeting schedules, sprint timing, the process for reviewing and defining sprint scope, testing procedures, client and developer responsibilities, and team roles. If possible, a price-per-iteration pricing structure, detailed in the MSA, can increase predictability of the overall cost of the project, as long as the client has an experienced person involved in the process who can manage the number and scope of iterations.

Agile presents a great alternative to traditional development in the right circumstances, but it is full of traps for the unwary. Focusing on the key challenges and working with experienced agile team leaders and legal practitioners can help maximize your chances of success.

Endnotes

[1] https://www.agilealliance.org/agile101/ and https://www.agilealliance.org/agile101/agile-glossary/